Travel by Coach and Canal was first published in the Kildare Archaeological Society Journal on January 1 1946.

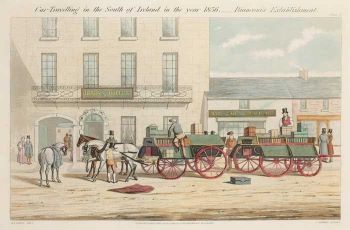

‘Since the establishment of the Bianconi coach services in the south of the country in 1815, the amount of traffic on the roads has increased considerably. In twenty years, Bianconi had 300 horses on the road and it was possible to cover eight to nine miles an hour at 1 ½ d per mile. Before the railways put an end to this service in 1865, he had 900 horses travelling on 4,000 miles of road.

Due to its good position on the main roads, Naas was very well served, no less than eight coaches a day left the various inns for Dublin. The timetables show that the coach for Carlow, travelling via Naas, Kilcullen and Castledermot, left the city at 9 a.m. and reached Carlow at 2.30 p.m., the fare was 8/4 for the somewhat cramped seats inside or 5/- if you took a chance with the weather and sat on the roof. It cost 16/- (or 11/4) to travel from Dublin to Limerick. Private cars could also be hired and a jaunting car left No. 86 Thomas St., Dublin for Naas each day.

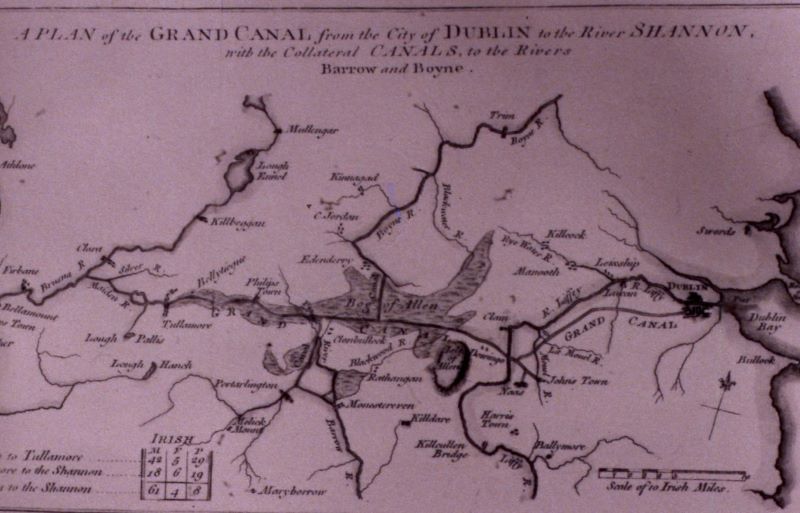

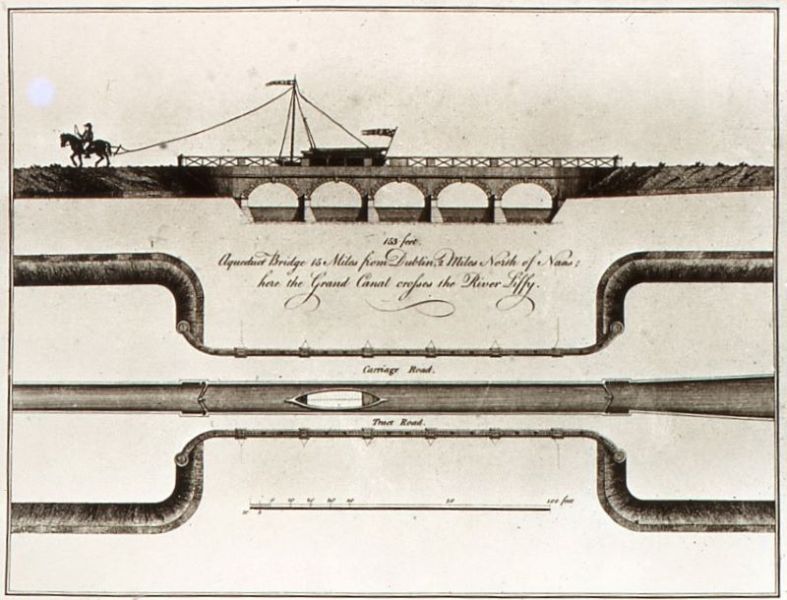

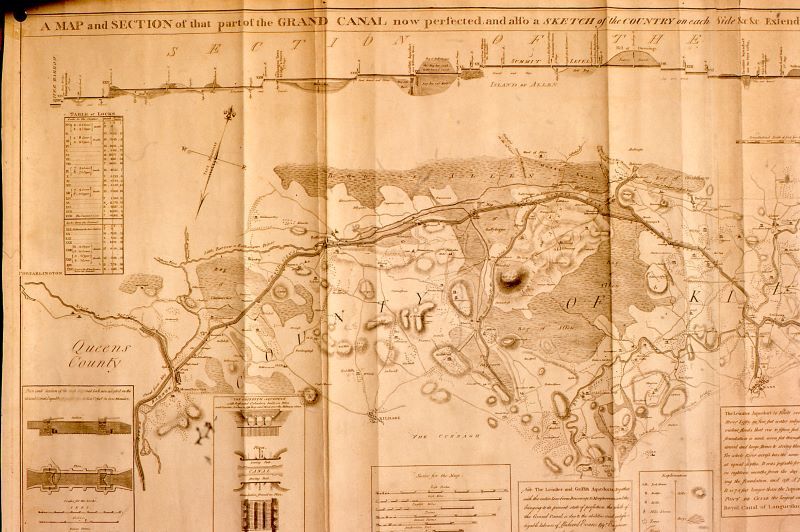

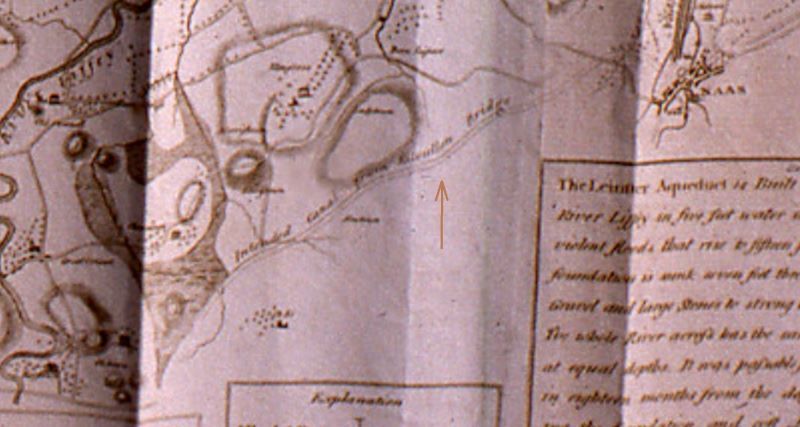

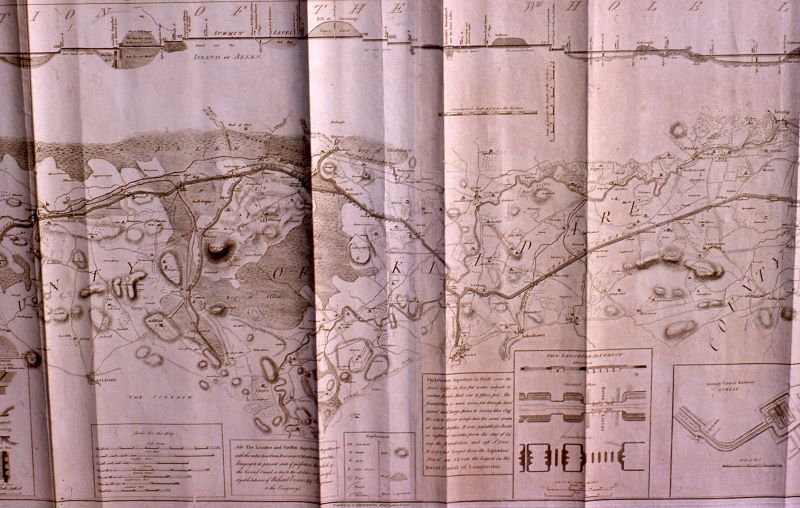

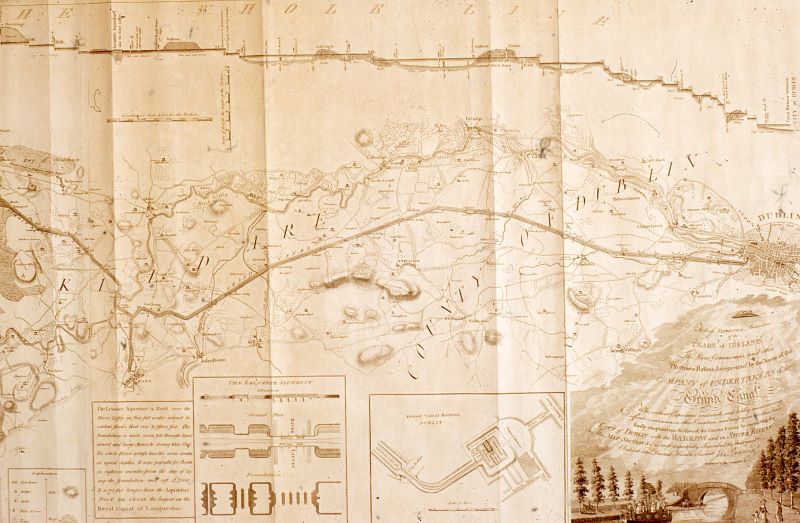

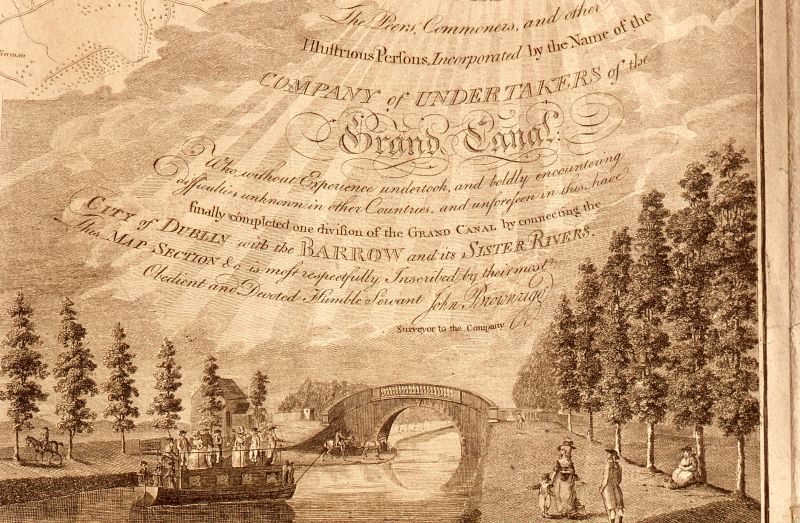

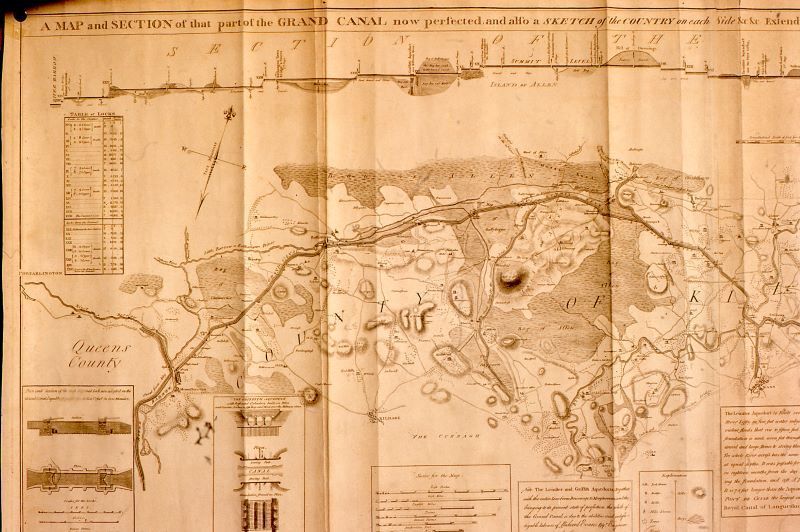

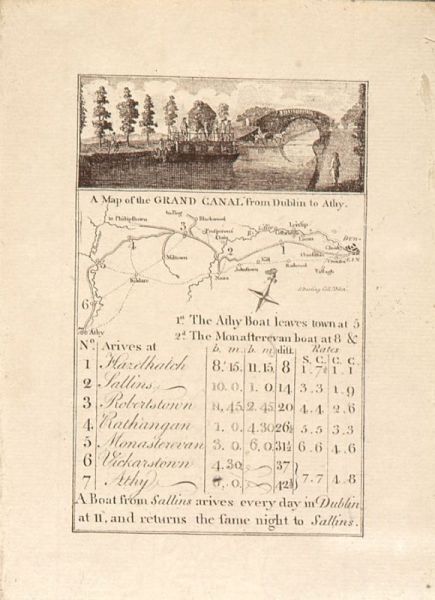

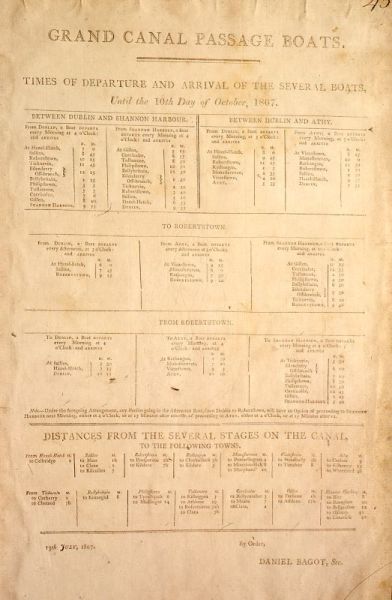

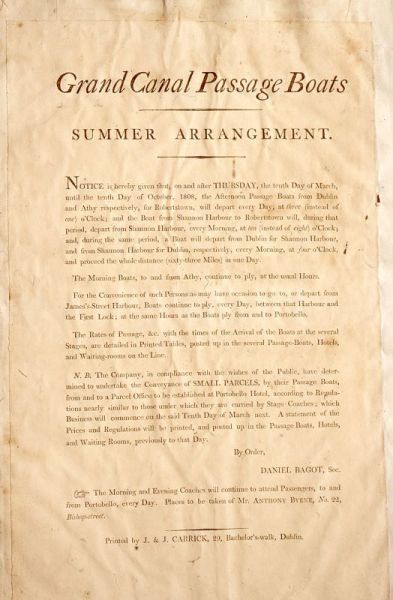

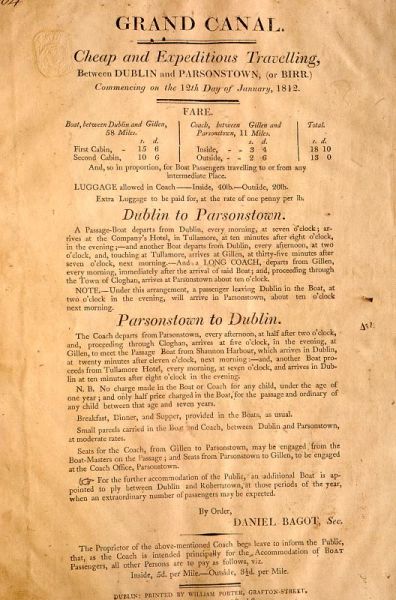

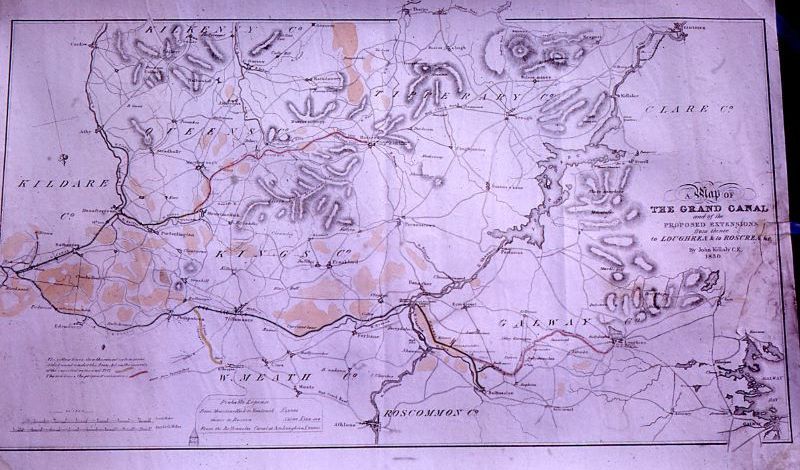

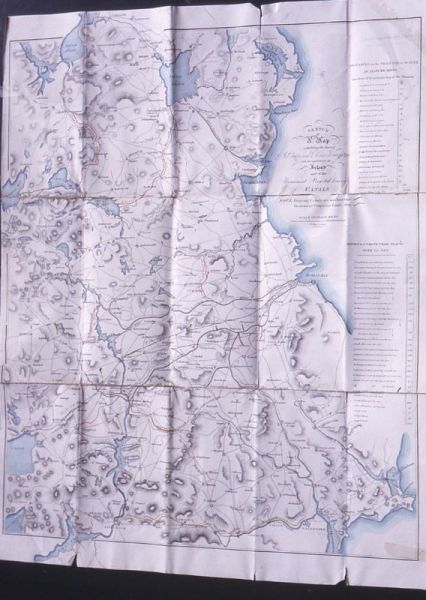

Travellers were not confined to road transport only but could go by canal boats. Construction of the canal system had been commenced in 1756 but due to the slowness of the work, the Board of Governors earned for itself the name “Company of Undertakers”. It took thirty years to complete the line to Monasterevin and the branch from Sallins to Corbally Harbour was opened in 1798 (Ed. 1810) having cost £12,300. During the Rebellion many people found it safer to travel by water than by road and the comfort of the boats was considered far better than the jolting of the coaches.

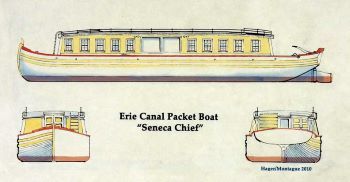

Fly or Swift Passage Boats, which travelled by day, were drawn by two or three horses at a gallop. These boats, very narrow in the beam, were about 35 feet long and the seats inside were comfortable with a fine view through the windows. Despite the lack of space, excellent meals were served on board and as it was also possible to promenade on the roof of the cabin, a good appetite could be worked up.

Within living memory, a woman who lived in Milltown, often told the story of her honeymoon trip to Dublin when, after spending a night at the Canal Hotel in Robertstown, she continued the happy journey to the metropolis by Fly Boat. Sir John Carr, an Englishman who visited here in 1805, left the following account of a trip to Athy in his book The Stranger in Ireland: “We slipped through the water in the most delightful manner imaginable, at the rate of four miles an hour. From Athy to Dublin by water is 42 miles and the passage money is ten shillings and ten pence. The day was fine, the company very respectable and pleasant. We had an excellent dinner on board, consisting of boiled mutton, a turkey, ham, vegetables, porter and a pint of wine each, at four shillings and tenpence a head. We slept at Robertstown, where there is a noble inn belonging to the canal company, and before daylight set off for Dublin.”

The poorer section of the community travelled by the much slower, and cheaper, night boats. Canal rates for the carriage of goods in 1807 were 1d per ton per mile for corn, grain, potatoes, sand, fuel and for “all military bodies with baggage, arms, ammunition and cannon, on their route.” By the eighteen forties the service had become integrated with the coach services and between the two systems the country was well served.

The canal service was used by many of the emigrants leaving this part of the country to travel to Galway to connect with the transatlantic steamers and a story is told locally that many of these poor travellers were murdered for their fares while staying overnight in the canal basin area in Naas. The fact that several skeletons were discovered in this area some years ago has given further material to the story-tellers. The finding of these remains might be more reasonably explained by the fact that a friary and cemetery, which is shown on old Ordinance maps and a map of 1722, stood at the corner of Basin Street and Back Lane; or the remains could be those of Famine victims or casualties of the 1798 Rebellion.’